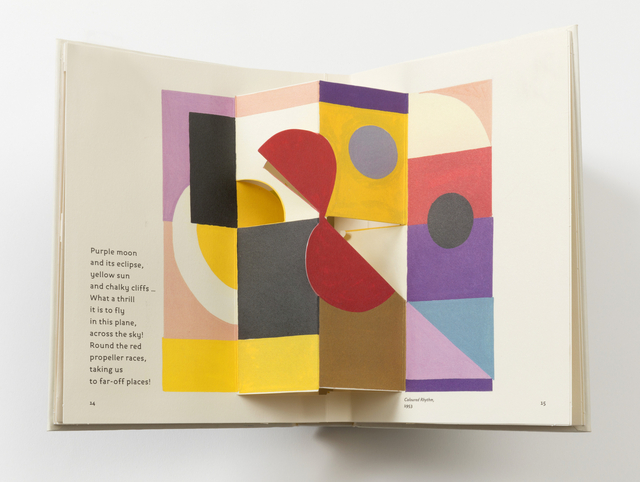

Making Design: Recent Acquisitions

https://www-6.collection.cooperhewitt.org/objects/18704475/

- engraving, etching in blue, black and red ink over gold leaf, with additional plate inked in mauve and green, à la poupeé, on off-white laid paper

- Museum purchase through gift of George A. Hearn

This print by Louis-Marin Bonnet shows a fashionable woman cooling her coffee in a saucer, an elegant way to consume the beverage popular in 18th-century France. Created “in the chalk manner,” Bonnet’s colorful print uses multiple inked plates to achieve a fine quality of engraving that mimics the effect of pastel. His additional application of gold leaf to the frame creates a rich image and evokes a portrait miniature.